GUEST BLOG

The Sultan of Swat and the Saints

By Dave Kaplan I July 15th, 2022

Babe Ruth never played for the St. Paul Saints. But the incomparable, lovable big fella, who revolutionized America’s pastime, prominently figured in the interwar era (1920-40) of Saints history.

That’s why there’s a section in the City of Baseball Museum on him, which now features a Babe Ruth-autographed baseball (arguably the most iconic signature in sports).

Babe was no stranger to Minnesota. Almost one hundred years ago, Oct. 16, 1922, the Sultan of Swat came to the town of Sleepy Eye with Yankee teammate Bob Meusel as part of a 19-stop postseason barnstorming tour.

Babe loved barnestorming, which he called “one night stands” and usually consisted of an exhibition game against local talent. Described by a Nebraska newspaper as “the biggest show since Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey,” Ruth’s appearances were an unparalleled draw.

As it was almost four years later, June 16, 1926, when Babe went from Sleepy Eye to Pig’s Eye (a.k.a. St. Paul) with his Murderers’ Row teammates during the Yankees’ road trip in the Midwest. St. Paul officials expected a crowd of 25,000 for the much-hyped Yankees-Saints exhibition in Lexington Park, which had a 10,000-seat capacity. Alas the game was rained out. But Ruth delivered, as always. He belted booming drives in a rain-drenched batting practice, then spent the rest of the day autographing baseballs and whatnot, visiting children in a hospital (currently Gillette Children’s) and tossing autographed baseballs out of the St. Paul Pioneer Press and Dispatch headquarters (then St. Paul’s tallest building) on North Robert Ave.

The following year, Babe and the Yankees made a special trip to St. Paul in the middle of their monumental 1927 season. Nearly 20,000 fans crammed into Lexington Park on July 20, one of the largest crowds in American Association history, as Ruth and Lou Gehrig belted long ones in a 9-8 win over the Saints. A 42-year-old Winona man was so overcome with excitement he collapsed in the stands and died.

According to the St. Paul Pioneer Press, Ruth and Gehrig “spilled nearly a quart of ink autographing baseballs and scorecards for small boys.”

Of course, the mighty Yankees and minor-league Saints had a unique alliance. Bob Connery, a former scout for Yankees manager (and turn-of-the-century Saints second baseman) Miller Huggins, purchased the St. Paul Saints in 1925. Huggins himself secretly owned shares in the Saints.

Connery arranged the trips to St. Paul, and also helped develop a player pipeline to the Yankees in the 1920s and ‘30s. In fact, two of Babe’s Yankee roommates, Leo Durocher and Jimmie Reese, were former Saints. (One of Ruth’s early roommates Ping Bodie famously said of Babe’s late-night carousing, “It was like rooming with a suitcase.”)

Ruth, however, was most connected to another former Saint, Mark Koenig, who played in St. Paul in 1921 and 1924-25. A singles-hitting shortstop who batted ahead of Ruth and Gehrig in the lineup, Koenig drank with the Babe, played cards with him, and once even brawled with him.

And witnessed a prank on him after the 1927 exhibition game in St. Paul. That night, a few Yankees visited a house of ill-repute and stole the madam’s parrot. They brought it down to the train and stuck it in Ruth’s straw hat in an upper berth,

Traded in 1930, Koenig joined the Chicago Cubs in mid-August 1932 and helped spark the team to the pennant. Then he became indirectly involved in one of Ruth’s most iconic moments. As the Cubs faced the Yankees in the World Series, Babe was peeved after learning the Cubs had already voted his former teammate only a partial Series share.

“Hey Mark,” he hollered across the Wrigley Field infield, “who are those cheapskates you’re with?” A nasty verbal war between Ruth and the Cubs and their fans ensued. In Game 3, with jeers raining down on him, Babe allegedly motioned to the center-field bleachers before blasting a home run to the spot where he had pointed. His mythic “called shot” is a controversy and mystery that rages to this day.

After the 1935 season, Babe Ruth retired. He spent the last 13 years of his life waiting for the call to become a manager. It never came. Or did it?

“Babe Ruth May Pilot St. Paul Saints Next Season” headlined September 1940 newspaper stories across the country. When Saints manager Babe Ganzel announced he wouldn’t return the next year, Ruth’s advisor Roy Doan told St. Paul exec Lou McKenna that the slightly more legendary Babe might be interested in managing the Saints.

Ruth, by then 45 and increasingly bored, finally realized he might need an apprenticeship in the minors. But St. Paul’s offer to the Babe to manage never materialized. If it did, it simply wasn’t enough. One thing’s pretty much for sure. Babe Ruth would’ve been a bigger attraction than Babe Ganzel.

Graig Kreindler

By Dave Kaplan | August 7th, 2021

As it turns out, Edward Hopper and Graig Kreindler grew up nine miles apart in Rockland County, a northern suburb of New York City. Both attended art school in the city, and both transitioned from illustrators to imagination-stirring artists.

Of course, they were born nearly a century apart (Hopper in 1882, Kreindler in 1980), so other commonalities are probably few. But, as a certain president likes to say, here’s the deal: While Edward Hopper was the most iconic 20th century realist artist of Americana, Graig Kreindler, fellow realist, is the foremost painter of America’s pastime.

A self-described visual historian, Kreindler’s baseball artwork may best be described as hyper-realistic. He paints subjects and scenes from every era of the game. Known for his maniacal research and uncompromising accuracy – “I’m relentless with the quality of work I expect of myself” – Kreindler’s results are consistently brilliant.

Despite countless accolades and awards over nearly two decades, he remains exceedingly modest about his success. Kreindler wasn’t sure he could actually make a living of it until he saw Bob Feller’s reaction to his precise rendering of the legendary pitcher’s 1940 Opening Day no-hitter on a cold, overcast day in Chicago. “That’s the best damned painting I ever saw,” Feller raved.

Kreindler’s artistry can be found in private collections, on Topps baseball cards, and in institutions such as the Baseball Hall of Fame and the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, where over 200 of his portraits (“Black Baseball in Living Color”) was exhibited last year as part of the Negro Leagues’ centennial.

And now two of Kreindler’s masterworks, spanning exactly 100 years of St. Paul Saints history, are a permanent part of the City of Baseball Museum. There’s an exquisite color portrait of George Halas, an outfielder on the American Association Champion 1919 Saints before he helped pioneer professional football as coach and owner of the Chicago Bears. And there’s “Sioux City Sweep”, a recently completed painting of the 2019 Saints celebrating their comeback victory over the Sioux City Explorers to win the American Association Championship, their first in 15 years.

On Aug. 5th, the Saints honored that team by retiring longtime manager George Tsamis’ No. 22 (which is now on display in the museum). Also, the first 1,500 fans in attendance for the Saints-Louisville Bats game received a special print of Kreindler’s, capturing that scene on Sept. 14, 2019, which was based on a photo by Kelly Hagenson.

That jubilant moment presented a different challenge for Kreindler. “It was weird, in a good way, a wave of action undulating through the painting,” he said. “There’s nice motion to it, the thing that really attracts you to it.”

Kreindler was attracted to drawing early on. As a pre-schooler, he drew cartoons “GI Joe, He-Man, that kind of stuff,” he said. Around that time he also began rummaging through his father’s 1950s Bowman and Topps baseball cards (the ones his grandmother didn’t throw out), which were illustrations. “I was just a kid but thinking, “Hey, somebody actually drew and painted these things – they’re not photographs, they’re made by humans. Maybe that’s something I can do,” he said.

Yet when he entered college, his plan was to become a sci-fi or fantasy book illustrator. A turning point came in portfolio class, when he was assigned to illustrate a “relationship.” He immediately thought of the pitcher-batter relationship, then decided to create a painting of Mickey Mantle, his father’s favorite player.

Kreindler delved into researching every detail – the vintage uniforms, the wall advertisements, the day’s actual weather. Since the painting was of his father’s fave, it had to be Mickey Mantle in every imaginable aspect. So began an obsession for exactness in every painting.

And his paintings can be both a work of art and a history lesson. His Negro Leagues project tells the story of the earliest Black and Latin American players, civil rights pioneers of their day. And his remarkable panorama of Lou Gehrig’s moving farewell speech in 1939 embodies the adage of a picture being worth 1,000 words, says MLB historian John Thorn.

Kreindler’s love of baseball comes from his father, who named him after Graig Nettles, the Yankees’ star third baseman in the 1970s.

Graig Kreindler hasn’t considered what he’d have been named if Nettles, who began his career with the Minnesota Twins in 1969, had not eventually made it to the Bronx. “Bucky Kreindler?”, he said with a chuckle. “I honestly don’t know.”

So what should people know about Graig Kreindler, painter of America’s pastime, that they may not already?

“That I’m eternally grateful I’m able to do this, and incredibly blessed to make a living off it,” he said. “I never take any painting for granted, and that 150% of my being, every piece of my soul goes into each piece.”

SPACE JAM

By Dave Kaplan | July 16th, 2021

For notable socio-cultural events, 1996 was hardly lacking. A couple of Stanford bros created a search engine for the Web (it’s now called Google); Fox News and MSNBC debuted; Madonna played Evita on Broadway; Prince Charles and Princess Diana divorced; Oprah introduced a book club; Tickle Me Elmo sold like crazy; the Spice Girls became girl power icons.

Also 25 years ago, Space Jam – not your normal Hollywood movie - struck pop culture gold. The ingenious teaming of a cartoon legend, Bugs Bunny, and basketball deity, Michael Jordan – His Hareness and His Airness – became more than a jubilant fusion of live-action and animation. It became a global blockbuster and beloved classic.

Click here to watch the Space Jam (1996) official trailer.

Released on Nov. 15, 1996, a year after Jordan returned to basketball after a brief attempt at baseball, the plot was, well, cartoonish. Michael and Bugs joined with the rest of the Looney Tunes to take on the villainous “Monstars” in a high-stakes hoops game. Now a quarter century since that climactic intergalactic contest comes the sequel starring LeBron James: “Space Jam: A New Legacy.”

The reboot has some big Air Jordans to fill. The original Space Jam’s juxtaposition of human and animated characters was the brainchild of legendary producer Ivan Reitman, and skillfully directed by Joe Pytka. The film rocked box offices worldwide and remains the highest-grossing basketball movie ($290 million in the U.S.) ever made. It stretched the unrivaled marketability of Jordan, the dominant star of the 1990s, spurring over $1 billion in sales of branded merch.

Space Jam is no doubt a cultural touchstone. And it has a unique connection to the St. Paul Saints, who will celebrate the film’s 25th anniversary with an exhibit in the City of Baseball Museum and special promotion on July 16 when the Saints play the Columbus Clippers.

The 2021 Saints ball pig “Space Ham” (distant relative of Porky Pig?) will be there.

And featured in the exhibit are film-worn items of actor/comedian and Saints part-owner Bill Murray, who wore a Saints cap in his supporting role as a Tune Squad walk-on. (Murray’s Air Jordan 2 sneakers and outfits are courtesy of Elliot Tebele).

Space Jam was buoyed by NBA star cameos, including Charles Barkley, Larry Bird and Patrick Ewing. Wayne Knight, the neighbor Newman on “Seinfeld” – a mid-1990s cultural phenomenon - played Jordan’s publicist in the film. And Jordan played himself, the greatest player of all time.

But Murray was Space Jam’s secret weapon, the ultimate role player who assisted Jordan, his real-life golfing buddy, on and off screen. Similar to his famed improvisational (“It’s a Cinderella story”) scene in the 1980 classic Caddyshack, Murray wasn’t originally scripted to appear in the critical basketball scene, where he gives orders to the Tune Squad.

Murray: OK, here’s how I see it. Duck?

Daffy Duck: Yes.

Murray: You kick it in to the girl bunny. Down in the post. Then you dish it back out to the guy bunny.

Lola Bunny: Got it.

Murray: Swing it around to Mike, over here. You go to the hole and dominate!

Michael Jordan: Bill! We’re on defense!

Murray: Whoa, ho ho! I don’t play defense. OK, you’re gonna have to listen to Mike on this guys, listen up.

Michael Jordan: OK, somebody steal the ball, give it to me, and I’ll score before time runs out.

Murray: Don’t lose that confidence, OK, paws and wings in here, all right!

By the time Space Jam hit theaters, the Saints were coming off a thrilling 1996 Northern League championship. Murray, along with Mike Veeck and Marv Goldklang, had founded the independent minor-league team four years earlier, instantly becoming the wacky rebels of baseball.

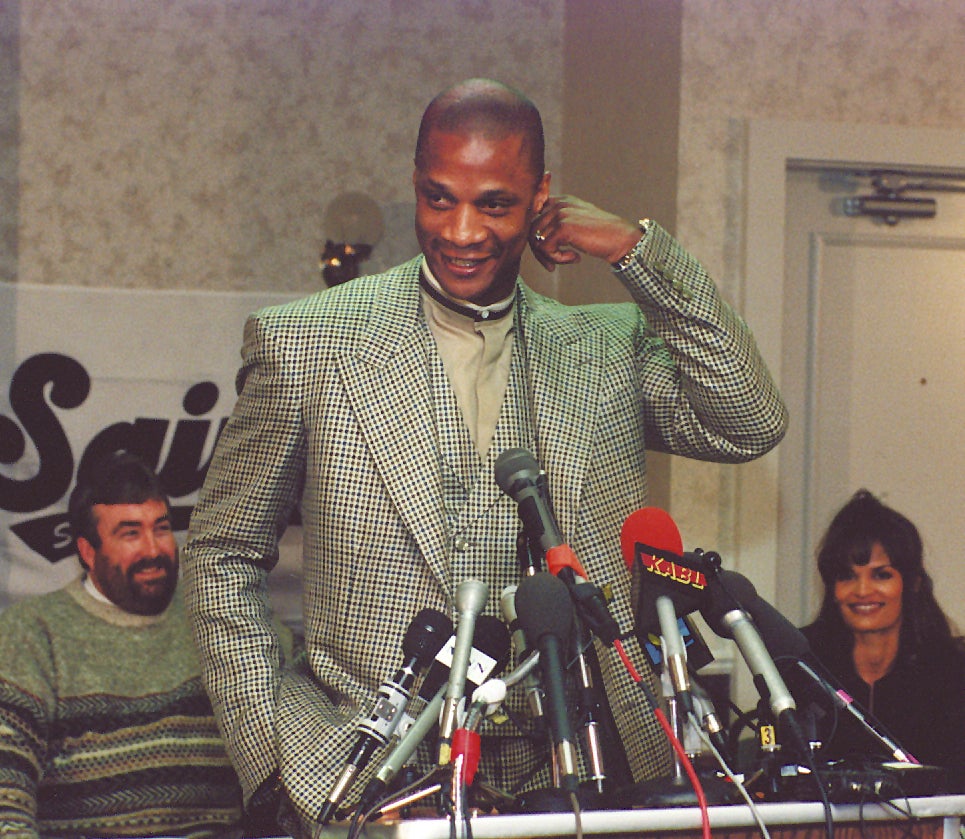

They were renowned for zany promotions and second chances. The ’96 Saints played before packed crowds in Midway Stadium, where a tuxedo-clad, 350-pound pig named Tobias delivered baseballs to the home-plate ump. And they salvaged the career of troubled slugger Darryl Strawberry, among others. Out of baseball due to substance abuse, Strawberry regained his focus in St. Paul, hitting .435 and 18 homers in 28 games.

Goldklang convinced the still-wary Yankees that Strawberry could help them and he did. He helped the Yankees capture their first world championship in 18 years, resulting in a ticker-tape parade down the “Canyon of Heroes.”

Shortly afterward, other heroes - the animated and live-action ones of Space Jam - arrived in theaters. Now 25 years later, their whimsical high-flying, high-tech adventure continues.